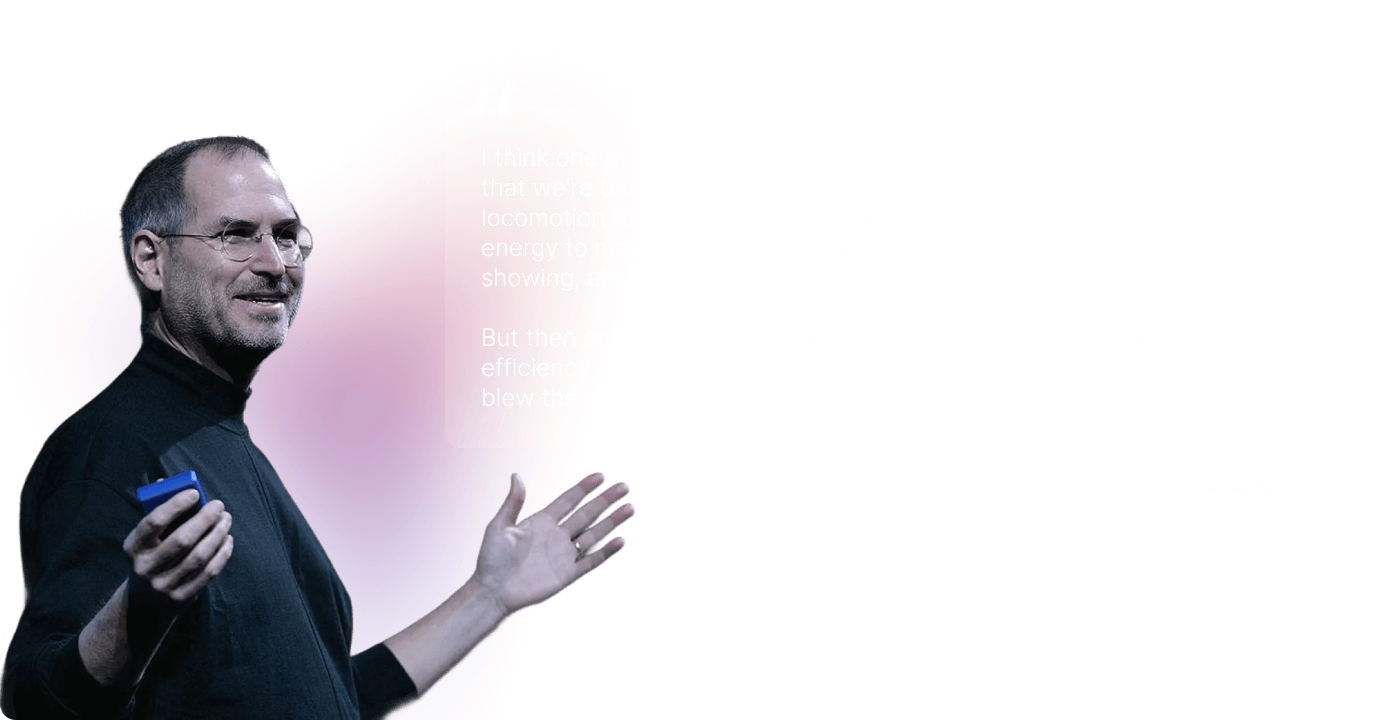

There's a Steve Jobs quote I keep coming back to:

Humans aren’t the fastest or strongest. But give us the right tool—something as simple as a bicycle—and we outperform everything else.

I think about this a lot in the enterprise B2B space. How do humans actually get work done? We use three things every day:

Reasoning. We assess the situation, understand the goal, figure out constraints, then decide what to do and in what order.

Tools. We pick the right one for the job, whether it is laptop, spreadsheet, CRM, internet, ChatGPT to get the job done.

Communication. We keep people in the loop, share context, adjust based on feedback.

If we want AI agents that operate in enterprise workspaces the way humans do, we need to capture that same model. That's why we built Docket on a custom cognitive architecture.

Today, everyone has access to frontier LLMs. OpenAI, Google, Anthropic…the ingredients are on the shelf for anyone to use.

So why do some AI systems deliver value while others hallucinate and break?

Same reason your favorite restaurant makes better food than everyone else with the same ingredients. It’s not the flour or the tomatoes. It’s how they put it together. The technique. The system. And how they tweak the recipe based on feedback from every plate returned.

In AI, that system is your cognitive architecture: how your agent reasons over time, manages memory, uses tools, adapts and decides when to think deeply versus respond quickly.

The problem we kept seeing was simple: most teams try to make one LLM call and do everything at once. Understand, plan, act, respond—all in the same breath.

This can look great in a controlled demo where the input is simple and predictable. In real usage, it tends to break.

We learned this the hard way. That's when we made the bet that became Docket's foundation.

We built on a pattern called Thinker–Responder (known in research as Reasoner–Talker). It mirrors Daniel Kahneman's System 1 and System 2 thinking, mapping how humans actually work.

In our architecture:

The Responder handles conversation in real time. It keeps tone consistent, answers clarifying questions, pulls from memory. When something looks complex or high-stakes, it hands off.

That gives you a clean separation between talking and doing. When those blur together, you lose control. You can’t see what’s about to happen. You can’t intervene before damage occurs.

The Thinker does the hard reasoning. It builds a structured view of the task, creates a multi-step plan, calls tools in order, handles errors. Most importantly: it produces a plan before it executes.

That plan is your choke point. You can log it, enforce policy on it, and require approval for risky actions. You can answer "what did the agent intend to do?" in a way auditors and customers actually understand.

You don't get that when everything lives inside one opaque LLM call.

The Tool Registry manages what agents can actually do. Tools are typed, governed capabilities and not raw API access. Each tool has strict schemas, scoped permissions, and defined failure modes.

The upside is simple and powerful: extensibility. Add a tool → the agent gains a new ability. Just like humans picking up a new tool, not growing a new limb.

Note: If you’re curious about the details, I’ve broken this down in a longer write-up.

We believe all the enterprise applications have to take some form of this architecture to make sure the agents we build are: :

.png)